In a world where the impacts of climate change are increasingly becoming a reality, adaptation has never been more crucial. By making adaptation a priority, we can proactively minimize vulnerabilities, enhance resilience, and safeguard the well-being of present and future generations against the unavoidable consequences of a changing climate.

In fact, the United Nations estimates that adaptation in developing countries could reach $300 billion/year by 2030 and $500 billion by 2050. With so much at stake, what are the dangers of getting adaptation wrong, what is maladaptation and why does it matter?

What is maladaptation?

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) defines maladaptation as

"Actions that may lead to increased risk of adverse climate-related outcomes, increased vulnerability to climate change, or diminished welfare, now or in the future."

Maladaptation can do more harm, even when the intention is good. An example of this could be a company wishing to plant trees to sequester carbon, but doing so in a location prone to wildfire. Consequently, when the trees start burning, they release more carbon into the atmosphere than they have had a chance to absorb.

A hotspot for carbon offsets, the Californian wildfires in 2021 are a tragic example of what can happen when strategies fail to account for climate risk.

Maladaptation is a major pitfall to avoid when addressing the climate change crisis. By issuing warnings around maladaptation, climate scientists intend to raise awareness about its potential to worsen the climate risk it's designed to alleviate.

The challenges surrounding maladaptation

Measures to reduce vulnerability to current or future climate hazards are steadily growing. Yet, adaptation efforts often time fall short, with an increasing number of cases where adaptation efforts remain insufficient.

One challenge are actions that may seem beneficial in the short term but ultimately exacerbate the negative impacts of climate change or increase vulnerability to its effects over the long term. For example, building seawalls, dykes, and flood control gates to adapt to sea-level rise and storm surges might seem beneficial in the short term, but are inflexible and difficult to change to adapt to future risks.

They also expose communities to more risks. In Fiji, seawalls built to protect communities from sea-level rise are now facing drainage problems from stormwater Instead of sea walls, scientists have suggested using nature-based solutions like mangroves to help protect communities from storm surges.

We must act by making climate-informed decisions

The paper, Maladaptation: When Adaptation to Climate Change Goes Very Wrong by Dr. Lisa F. Schipper from the Environmental Change Institute at the University of Oxford covers the subject intensively:

“Adapting to climate change is necessary to ensure that the impacts will not overwhelm societies and ecosystems around the world. But planning adaptation is an exercise in uncertainty, and built on imperfect information, many adaptation strategies fail. Some go even further, creating conditions that actually worsen the situation; this is called maladaptation. Aside from wasting time and money, maladaptation is a process through which people become even more vulnerable to climate change…Until adaptation projects directly address the drivers of vulnerability, however, maladaptation will continue to be a risk…” - Dr. Lisa Schipper

How do companies avoid maladaptation?

McKinsey’s research outlines that in a “business-as-usual” climate scenario, average global temperatures are estimated to jump between 1.5 and 5 °C by 2050 and the AR6 report from the IPCC illustrates how adaptation plays a pivotal role in climate risk reduction.

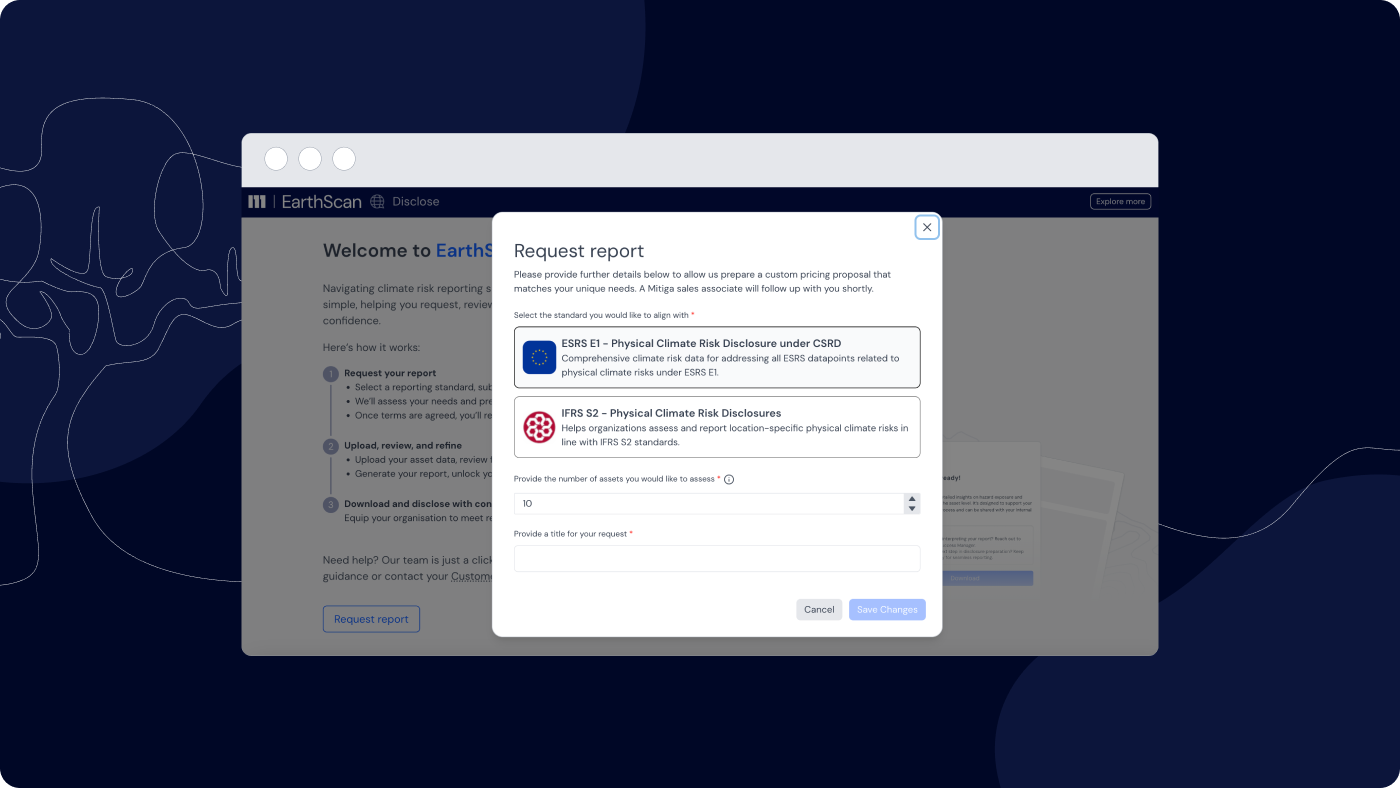

Every company must have a climate adaptation strategy in place. To do this, businesses must first discover which climate risks are likely to impact their assets, so that they can make informed decisions on how to positively adapt.

Creating effective adaptation strategies is only possible if governments and organizations understand climate-related risks at the level of individual assets they own, manage, or rely upon. Without this insight, decision-makers cannot determine which countermeasures - such as building sea walls or planting forest-based carbon offsets - will effectively de-risk their projects.

Previously, understanding climate-related risks at the asset level was nearly impossible due to the complexity of climate data.

However, advances in earth science and machine learning have made discovering and analyzing climate-related risks to individual assets possible.

By leveraging technology through products like EarthScan™, companies can access a clear, science-backed, and shared view of climate risk, and for decades to come.

Using technology to put climate at the core of every decision can guide companies away from making maladaptive mistakes, and instead, lead them towards architecting the effective adaptation strategies we need to build a more resilient future for our planet.